For those of you who prefer to read on paper rather than a screen, here’s an easily printable pdf file of this story.

Dad was younger than I am now when he passed. It’s strange to think about. I remember him as a man- lean, upright, the linger of aftershave on him but still with a near-blue shadow of stubble at his jaw and cheeks. I’m eighteen months older than he ever got to be and yet I still feel like a boy.

He was cut down by stomach cancer- rare and progressive and merciless- at thirty four years of age and he went from athletic and tanned and quick with a smile to a hollow eyed, sunken cheeked, still-smiling near corpse in the span of a few weeks. As I remember it he was diagnosed at the start of the summer holidays and by the time I was back in school he was gone.

But not completely. I still see him in dreams most nights. He is indistinct and faint like an image that has been photocopied again and again, or like a scene on VHS that’s been warped and worn by constant viewing and rewinding. In these dreams, these glimpses, he says things that make no sense, things which fade from memory before I can bring my eyes into focus and stretch my fumbling hand to my bedside pen and paper.

I also see him in the bathroom mirror from certain angles, and sometimes he’s looking back at me as I watch the barber scissor my hair. And all of these years later my heart will still leap when I make out what I think is his silhouette in a crowd or when I hear someone shout out his name, as if they too are searching for him. And then I will see that it is the shape of some stranger, or what I heard was in fact a mother admonishing a child or a man greeting his friend by calling him by his name. And with my heart still beating in my ears and with a swirl of anticipatory nausea still in my gut I will smile a half smile and linger in a memory- the funeral, the hospice, a Christmas, a birthday- before continuing on with my day, the stranger oblivious to the drama, to the up and the down that has just played out in my head. And then I walk on, just another body ambling through the crowd.

Dad was twenty three when I was born. By that age he had already left school, found his soul mate, married, found his vocation and put in enough overtime to pay the deposit on a house. He knew what he wanted in life- descendants, security, stability- and he sprinted to get each thing, one after the other. Maybe he knew that he was in a race against time. I mean, we all are of course. But maybe he knew that his was going to be a short race and that he didn’t have time to fool around with hesitancy, with second guessing or circular ruminating or with carefully weighing up what was in the one hand and in the other. I don’t know- I never got the chance to ask him.

What I do know is that his race was short. What I do know is that I am still stuck on the starting line, waiting for a sign, for the lights to change.

See, I lost my job a little while ago. Lost my girlfriend too. Those things have a way of going hand in hand. She wasn’t a girl and she wasn’t my friend, come to think of it. She wasn’t my partner either, whatever that means. So jobless, loveless, rootless and essentially moneyless I hired a car and drove two suitcases and six cardboard boxes of stuff across country to Mum’s house. To the house Dad’s overtime had won for us.

So here I am back in my childhood bedroom, a mausoleum to my teenage obsessions. Coming on for two decades into my own race and I have got precisely nowhere.

Fuck.

It’s all exactly as it was- the single bed, the flat pack shelving, the paperback collection of a pretentious, would-be intellectual, a few volumes with creased spines and dog-eared pages but most of them pristine totems, signifiers of my desire to belong among those who think they are too special and clever to belong. Looking at them I don’t know whether to bin them or to maybe actually finally read them. They came after Dad was gone, the books, so I don’t know whether he would have approved of them or not. Maybe not. Maybe that was the point. That old song says You Can’t Put Your Arms Around a Memory. And you can’t really rebel against one either, because you never quite know if you are getting the reaction that you seek. We test boundaries so that we can feel where we are in the world. A counsellor told me that once. But ghosts are untouchable. You go right through them.

I’d called Mum before I came back home. We hadn’t spoken, really spoken- as opposed to exchanging small talk and reassurances that we were both doing fine- for a long, long time. As we talked and one hour ticked over to the next and the next, I realised that our fixed weekly reassurance ritual hadn’t counted for much. Waiting for my turn to speak instead of listening, trying to wind the conversation down and get off the line before it had barely begun, that sort of thing. How most people go about it I imagine. Not sure that excuses it though.

So I had laid it out for her, the whole mess, the whole work falling apart due to management games- stuff that I’m not going to get into here- and the whole falling out with the girlfriend who was neither a girl nor my friend. The dissolution of the partnership, so to speak. She listened and let me go on and then said ‘so what are you going to do?’

I had no idea. I’m not sure I ever have.

‘Move back here for a little bit.’ She said. ‘Get back on your feet.’

I made some face saving protestations, but as soon as she said it I knew I was going to do it. It’s probably why I called in the first place, in terms of what outcome I was hoping to get. I remember being relieved I hadn’t had to outright ask. And ashamed that it had come to this. Back at the starting line. Thirty six years old.

I wanted to be useful, I wanted to help out. I made that known as we ate takeaway at the dining table that first evening, after I had unloaded the two suitcases and six cardboard boxes from the rental car. I paid for the food- I had to insist- and I left a generous tip for the delivery driver though I was pretty sure my bank account was already hovering on the threshold of being overdrawn. You could say that this generosity was a form of deceit, a way of bolstering up the image that I was doing okay. And it probably was. But sometimes these things make you feel good or at least like you are normal. Like things are going to work out.

Between bites I gave out unsolicited reassurances that I had a plan (I didn’t), that I had a few leads to chase down regarding getting a new job (I didn’t) and that I was coming around to seeing this whole situation as being an opportunity (I wasn’t). I may have used the phrase ‘blessing in disguise’. Mum smiled while I prattled on and nodded and made positive, encouraging, affirming noises. Maybe she was afraid of the engulfing silence and sadness that would descend if I stopped talking.

I wanted to help. Mum pointed out that there was a roof space full of old toys and gadgets and schoolwork and photographs and such that I could sort through if I wanted too. Keep what I want, dispose of what I don’t, sell what might be collectable now or have any value. Something to occupy my mind while I was waiting for the (fictional) job leads to play out. A little project.

I agreed. Maybe this would be a helpful thing to do, maybe Mum had more guile than she let on and this was a make-work project, a ploy, because she knew that I was lost and holding on and that the blessing in disguise veneer was already on borrowed time. Perhaps she could already see the cracks.

The next morning I was woken by the sound of birds. It was an annoying, strangulated, post sunrise squawking, not some idyllic countryside birdsong serenade. I lay there for a good thirty seconds trying to work out where I was and how I’d got there. From the bed I saw the wall of tacked up rockstars cut from music magazines, with a giant Johnny Cash, monochrome and furious, giving me the middle figure as the centre piece. I remembered where I was.

Mum made us tea and toast and we watched the breakfast news show, punctuating our silence with the odd comment and aside about each topic. The show went from tragedy to banality and back again- war, earthquakes, corruption, moral panics, the best clothes to buy to ring in the new season, superfoods, celebrity gossip, skincare tips. From atrocities to bakery, the hosts reading from the autocue and modulating their voices so that we knew how we were supposed to feel. I wanted to hurl my mug through the screen.

‘I’ll make a start.’ I said through a yawn as I pushed up from the settee and stretched out my arm and neck muscles. Anything to pull me away from having to endure anymore daytime TV.

I found a stepladder and wobbled up it and pulled myself through the hatch and up into the roof with a torch clamped between my teeth. I crouched low and duckwalked around the small patches of space that weren’t filled with timeworn boxes and tied up bin liners stuffed with God knows what. Clearly none of this stuff had been looked at in years, decades. I had thought that Mum had parted with Dad’s stuff soon after he died, passed it on to friends who might have been interested, donated it, thrown it- to sever herself from constant painful reminders- but maybe she had just shut it all away up here. I dug around for the next hour or two in that hemmed-in dust and wood smelling world up there, lost in remembering.

Notebooks and schoolwork folders brought back memories of boredom and coasting through classes, waiting for real life to begin. Clothes- Mum clearly had kept every item, every scrap that any of us had ever owned- took me back to holidays and birthday parties and that I would never have thought of again and each memory was corroborated by album after album of photographs where the sun was always shining, the people were always smiling and the haircuts and fashion choices were always questionable.

The ones with Dad in- posing, smirking, always favoured by the camera and the centre of group shots- were both hard to look at and hard to look away from. I thumbed through them for hours and hours. It made me heavyhearted, tired, hungry. But I carried on. Once I had gone through every album, every image I returned them to their boxes and set them aside. And that was when, buried in the corner dust coated and forgotten, I saw it.

Christmas 1998. Our last one together. I was 10 then which means that I was still a few years away from the phase where you begin to feign indifference at gifts and pleasures and rituals. I remember being excited- that giddying, white hot, bouncing up and down excitement that seems to fade with the years and soon exists only as occasionally flickering embers before going out completely.

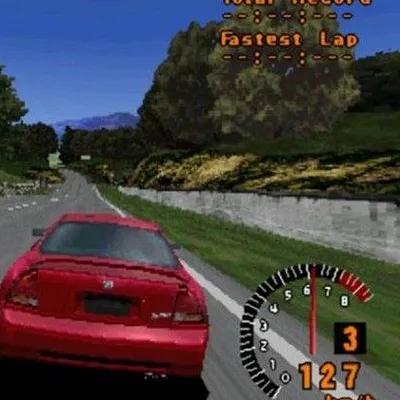

I remember tearing through the other gifts under the tree, getting it over with because they were the wrong shape, because I knew that they weren’t the one. The big one. I remember being made to leave the big one until last. I knew- or at least I truly hoped- and Mum and Dad knew that I knew. I remember tearing away the paper of the large box and seeing the silvery grey and knowing then that all of my prayers and pleading and letters to Santa (though I was getting fairly close to seeing through all that) had been answered. A PlayStation. And three games. The rest of that day- apart from the Queen’s Speech and the turkey dinner- was taken up with me and Dad sat cross-legged up close to the TV sweeping the direction buttons with our left thumbs and hammering down the accelerate button with our right as we drifted around different tracks in our supercars. And the next day and the next, it felt like. For hours and hours and hours.

It all came back in an instant, in a memory that I could feel in my chest and with images so sharp and so vivid that the chasm of years between now and then was obliterated in an instant. I wondered if the neglected and forgotten machine- the gift to end all gifts- still worked. I had to know. Nothing else mattered.

Johnny Cash and Keith Richards and Paul Simonon and all of them watched as I untangled cables and fiddled with remote controllers and television ports and mumbled threats under my breath. I made the thing work, I made the black vacant screen glow white and orange and the start-up chime sounding like a choir of angels made my arms goosebump. You can’t put your arms around a memory, but a memory can put its arms around you.

In the box along with the console and the controllers and the cables and the games there was a memory card- green plastic and see-through from that brief sliver of time when gadgets were candy coloured and transparent. I plugged the thing into its port and placed the car game into the tray and loaded up the game. I remembered everything- every menu, every sound effect and engine roar, every piece of music. The time between that Christmas and this moment disappeared as if it had counted for nothing- I was a boy sat too close to a television screen feeling emotions that I wasn’t yet grown up enough to be able to articulate.

The fastest lap held on the memory card was saved under DAD. The save date was late spring ’99. He had never let me win, never gone easy on me for the sake of making me feel better. He didn’t believe in that sort of stuff, in those kinds of hollow victories. This replay, this ghost race demonstrated that as his Japanese supercar- the Nissan Skyline that he had always played- hugged corners and drifted through chicanes and kept to a tight and disciplined racing line.

I had to beat it.

I chose the same Mitsubishi I had always used and faced off against Dad’s transparent pace setter. He left me for dust, again and again. I clipped tyre-walls overshooting corners, I spun out trying to aggressively drift to save fractions of a second. I swore a litany of fucks as my car in top gear was still too slow on the straight to the finish line. I tried again. I tried again. The flesh of my constantly depressed accelerator thumb started to ache. My eyes burned with tears. The room grew darker as the sun sank down behind the houses.

This was all that mattered.

Mum may have entered with a polite knock to see how the sorting was going, to see if I was hungry. I think I sent her away with a grunt. Maybe she just sensed what was going on, what I was trying to do. Maybe she hadn’t knocked at all.

Sometimes I could keep nose to bumper with Dad’s Skyline for the first lap or so, copying his moves and trying to cut inside whenever he gave up an inch or two of space. Sometimes I would go straight through his ghost car for a frame or two but I could never get out ahead. He was just too good, the same consistent unbeatable run, the same precise turns and strategies again and again.

My neck hurt. My eyes hurt. I couldn’t stop, he wouldn’t have wanted me to stop. Would he? Stupid fucking game. I tried again, a second off. Again- 1.2. Again- spinout, pause button, growl, reset. It was fully dark outside. I stood up stretched my neck, went to the bathroom across the landing, splashed cold water on my face and saw an image of two race cars seared behind my eyelids.

Again, a little closer. Again, closer. One more and then I’ll stop. Closer. One more. Within a second, the closest yet. It was maybe past midnight. One more. Spinout after holding the lead for a lap. One more. A second behind. One more.

My thumbs ached and my eyes burned and I sleeved away tears every time I yawned.

I started perfectly. I had the lead instantly. I took the first corner with the faintest tap of the handbrake, the tail drifting out and then back exactly with the contours of the track. I shifted gears with the shoulder buttons, my ears straining to pick up every detail of the engine noises. This was the one. The ghost car slid through my right rear wheel. I was breathing through my nose in a quick shallow rhythm. Was I breathing at all? I kept to the line on the straight, top gear, my accelerator thumbnail white, both hands threatening to cramp, my eyes just wanting sleep.

Come on come on come on come on.

I drifted around the hairpin that was usually my undoing, a squealing handbrake turn that turns anything less than perfection into a huge loss of speed or a jolt along the trackside grass. Perfect. And still he was right behind me, right on top of me.

The final straight, the stands, the finish line and the chequered flag drawing closer and closer. I was a car length ahead, then a half a car length. A second from the end.

I pressed pause. The nose of my Mitsubishi was a pixel away from touching the black and white chequerboard. Dad’s transparent Skyline was maybe a fifth of a second behind. When I unpaused the game I would win. I would end his record of over twenty years. I would surpass his victory.

I let the joypad fall from my hands.

I turned the console off with an aching finger and pulled the cable from the back of the TV.

And that was that.