For those of you who prefer to read on paper rather than a screen, here’s an easily printable pdf file of this story.

‘Is this really necessary?’

The guard sighed and pointed with the tip of his pen to the painted X on the floor. He glanced to his colleague who was stood to the left of the questioning prisoner.

‘Mr Wilson, would you be so kind as to assist Mr Pryce with his garments.’

Pryce had heard this same tone- this facetious mock-civility with its undertones of contempt, of threat- from every uniform he had encountered in this whole sorry year long process. From the officers who arrested him, to the detectives who offered him vending machine snacks in exchange for a confession; from the bailiffs who led him with a guiding mid-back palm to and from the witness stands and lobbies and vans, to the prison guard now giving him a resigned and world-weary look from behind his clipboard and ballpoint pen.

‘That’s quite alright,’ Pryce said, a slight quiver in his voice from the prospect of the looming Wilson. ‘I’m just, this is all rather out of the ordinary for me.’

‘I should hope so, Mr Pryce.’ The Clipboard Guard said with a wry quarter-smile.

Pryce handed Wilson his blazer which the guard carelessly dropped into a numbered cardboard box.

‘One light brown blazer, tweed.’ The Clipboard Guard said as he wrote.

‘Woollen, Mr Harrison. With darker brown elbow patches.’ Wilson said.

‘Right you are,’ Harrison said as he amended his paperwork.

Pryce unbuttoned his shirt with fumbling thumbs and struggled out of it.

‘One oxford shirt, white, with thin navy stripes.’

‘Hm, mm.’

Pryce slid one shoe off and then the other and then his trousers (‘Woollen trousers, charcoal’) and then his socks (‘black socks, peacock feather motif, small hole near right greater toe’) and then his underwear. He stood on the painted X now goosefleshed and hunched in shame, his thin hands cupped around his genitals.

‘Arms up above you head Mr Pryce.’

Pryce stood in a star-shape. Harrison ticked a box.

‘Palms open.’

Pryce complied automatically, mechanically, his gaze fixed on a metal sign stuck to the institutional blue-grey wall beyond Mr Harrison’s shoulder. The sign showed a series of stickmen contorted in semaphore shapes, each phase of the imminent full body search.

‘Open your mouth.’

‘Ahhh.’

Tick.

‘Lift up you tongue.’

‘Ahhh.’

Tick.

‘Stick out your tongue out, wider.’

‘Ahhh.’

Tick.

‘Good. Turn around. Lift up your right sole.’

Tick.

‘Now the left.’

Tick.

‘Bend over. Yeah, palms on knees.’

Pryce bent over, the painted X between his bare feet began to blur and wobble.

‘Now cough.’

Pryce forced out a single sharp cough. He wondered if it was possible to back out of the deal...

Pryce, his anxiety giving away to thought-erasing boredom, turned to look at his wristwatch. He saw nothing but the silver glint of a handcuff. This was the third or forth time he had done this, and every realisation that his wedding anniversary Brietling was now a loose steel cuff came as a fresh surprise. He squirmed in his chair- red moulded plastic and curved to encourage recalcitrant schoolchildren, and indeed recalcitrant prisoners, to sit up straight.

Wilson, stood silent by his side, exhaled loudly through his nostrils. The guard didn’t deign to look down at the overalled, bespectacled prisoner in his shadow. The prisoner’s delousing powder stink and the metallic squeaks of his squirming were irritation enough. Or so Pryce imagined.

Pryce looked vaguely at the opposite wall as he followed a chain of memories- the back arching plastic chair led him back to drab schooldays and then to the sanctuary of English classes and from there to looking out on lecture theatres and seminar rooms and black tie dinner tables as his younger self expounded on Shakespeare, on the structuring of the novel, on how gratifying it was to be recognised with an award such as this. And then his mind, being what it was, focused in on one particular student with her enthralled and naive eyes and her small town attempt at sophisticated dress and then her flushed and glistening late-teen body and her stifling a moan by biting down on a flower patterned pillow and her…

‘Mr Pryce.’ The voice was rich and soft, as soothing as a relaxation tape. Pryce turned to it.

The man in the doorway was mid-height and dressed in scholarly wool and corduroy. He was elderly but upright with a precise white beard and a barbered horseshoe of matching white hair.

‘Please come in, Mr Pryce. Mr Wilson will wait outside for you.’

Pryce stood and shuffled in his shackles through the doorway. Wilson gave a small nod of deference and exhaled loudly in spite of himself.

‘Take a seat Mr Pryce.’

Pryce lowered himself into the plush leather swivelchair opposite the even plusher, even taller chair of the old man. Between them was a rich, dark wooden desk. Mahogany maybe. The surface was clear, there were no pens or staplers or monitors or keyboards, nothing that could serve as a makeshift weapon.

The old man reached down to his side and Pryce heard the grating scree of a filling cabinet slide on its runners. The old man lay a thin manilla folder down in front of him, and Pryce scanned the upside down series of numbers and his own upside down name written in neat capitals.

‘It’s good to meet you, Mr Pryce, I’m Doctor Rose, as you may well already know. Now. It’s my role here to assess you, to ascertain the particular nature of your case and then to help get you situated as best as possible. Does that all make sense to you?’

It didn’t particularly but Pryce nodded and said yes all the same.

Doctor Rose wetted his thumb with his tongue and flicked through the opening typewritten pages of the file. ‘I’ve glanced at your case, Mr Pryce, and of course I am familiar with you by reputation, but old age does tend to make one a little forgetful of the finer details of things. If you’ll indulge me...’

Pryce swelled at the remark about his reputation and told the doctor that of course he could take as long as he needed.

'Thank you.’ Doctor Rose said, reading. He looked up from the page.

‘So I want to begin by just corroborating a few details here. I understand that the charge against you is the first degree murder of your spouse. Is that correct?’ The doctor’s voice remained rich and soothing, without a hint of judgement.

‘That’s correct, yes.’ Pryce looked down at the vast emptiness of the wood.

‘And you are wholly innocent.’

‘Yes, Doctor.’

‘I see. I apologise for having to make you relive the whole-’ The doctor searched the ceiling for the right word ‘unfortunate side of this affair, but mistakes sadly have been made in the past.’

‘I understand, Doctor.’

‘You never can be too careful. We had a case a while ago of a sculptor who joined The Programme with a conviction of statutory rape, and also a regular, garden-variety serial sex offender. Both had the name Jones, you see. A very common name of course. And so poor Jones the sculptor was mistakenly sent to the general prison while the other Jones, the brute Jones, was inducted into The Programme. Though he wasn’t an educated fellow, this imposter Jones soon cottoned on to the situation and unfortunately it became necessary for him to have a mishap. Had he been a mere thief, say, it may have led to prying eyes. As it was it very nearly led to the termination of our whole operation here. I can’t tell you the amount of paperwork and hand-wringing it took to make the situation right...’

This was the most that anyone had spoken to Pryce in days, the most, in fact, since the oblivious, grandstanding Judge had given him a ten-minute monologue on morality and the squandering of gifts to go along with the sentence.

‘But be that as it may, we continue onwards, Mr Pryce.’

‘Yes Doctor.’

The doctor wetted his thumb once again and skipped on to the next section of the file.

‘So according to what we have here, your wife- herself somewhat of a literary figure in her own right- is also a part of The Programme?’

‘That’s correct, Doctor. We were both tired of the grind of deadlines, signings, interviews, the whole situation. We were tired of each other too, most of all. She detested her family, and most of mine are gone, as is probably already written down in there.’ Pryce gestured to the file. ‘So it was perfect. She’s had the chance to start over- new name, clean slate- in one of your more women-centric facilities and I-’

‘And you get to join us here.’

‘Yes.’

‘Very good, Mr Pryce.’ The doctor made a quick notation in the margin of the file-page. ‘So just to clarify- and again, I may be being somewhat over-cautious after the Jones incident- you and your wife, upon learning of The Programme decided that you would fake her death, thereby allowing her to begin a new life under a new name, and allowing you- having been found guilty of her murder and thus ruining your reputation- to join us in The Programme.

‘That is exactly correct, Doctor. It’s funny how it already all feels so long ago.’

‘I’m sure it is. And I must take a moment to apologise for all of the, ah, distress that you have had to endure to get here. You see, when one wishes to rig a prizefight- for it to be convincing- only the loser must be in on the fix, as it were. If the winner were to know that the situation were a hoax then he would not behave authentically, he would not be able to sell the ruse to the spectators. And so every police officer, every judge, every lawyer and every guard that you have thus far encountered were led to believe that you were an actual cold blooded murderer. I trust you see the necessity of such deception.’

‘Yes, Doctor.’

‘Very well, then.’ The doctor turned to the final page of the file. He spun the file around one-hundred-and-eighty degrees and pushed it along with a black fountain pen towards Pryce.’ If you would be so kind as to read through this and sign at the bottom.’

Pryce had read more words- more prose and poetry and literary academic works- than anyone he had ever met. His ability to devour books whole was legendary in the bookish circles he moved in. But this single page document was beyond him- a blur that refused to come into focus. It may as well have been written in cuneiform. Pryce signed it anyway.

‘You seem perplexed Mr Pryce.’

Pryce fumbled for an evasion. ‘I was just, er, just wondering about money.’

‘Well, I’m sure you have many questions about the day to day workings of this facility. In fact...’ The doctor looked at his watch and then pressed the underside of his desk with two fingers.

‘Mr Wilson?’ He said to the ceiling.

The voice of Wilson, warped and tinny, responded from a speaker hidden somewhere in the high ceiling ‘Yes, Doctor?’

‘Is Mr De Boele here yet?’

‘He’s stood right next to me, Doctor.’

‘Excellent, send him in.’ The doctor’s two fingers reached for a second button and after a sharp, high buzz the office door was opened and a man wearing the same standard issue overalls as Pryce entered.

The man shook the doctor’s hand warmly with his right and patted his shoulder with his left. He offered his hand to the seated Pryce whose shackled hand could only manage a weak, jangling shake.

‘Don’t get up,’ De Boele said to him, and then. ‘I’ve been looking forward to meeting you.’

‘Oh?’ Pryce said, scrutinising the man. He knew him from somewhere.

‘Absolutely.’ De Boele said, sounding like he genuinely meant it.

‘Good,’ The doctor said, turning to Pryce. ‘Mr de Boele here has been kind enough to offer to show you the ropes. He will be more than capable of answering any questions you may have...’

‘Be my pleasure.’ De Boele said. He adjusted the beanie he was wearing. It was cuffed over so that it wasn’t much larger than a skullcap and it sat at a rakish angle on the man's closely cropped head.

‘Wait,’ Pryce said, remembering a similar looking man on television once, a younger man, junkie-thin wearing a similar woollen beanie at a similar tilt. ‘Seb de Boele?’

‘The one and only.’

‘My God. My wife used to rave about you. She never missed one of your openings. Of course that was before you-’

The doctor interrupted with a cough. ‘Mr De Boele, if you could tell Mr Wilson that our new arrival has been fully processed, he will be able to have these unfortunate restraints removed.’

‘Of course.’ De Boele said with a smile in his voice. He beckoned for Pryce to stand and put a friendly guiding hand on his shoulder as he motioned the shackled prisoner towards the door.

‘Oh and Mr De Boele.’ The doctor said. ‘Be kind.’

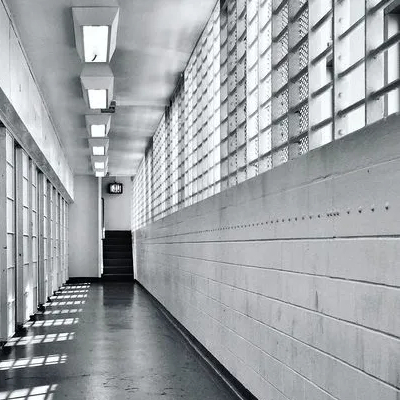

The two inmates walked and talked. Pryce still took the short strides of a man accustomed to being restrained while De Boele strolled the corridors with the ease of a boulevardier taking in the lunchtime sun.

‘Yes, my brother, this is paradise.’ De Boele said gesturing to the rows of numbered metal doors on one side and the barred windows on the other. Beyond those bars was the yard with its basketball hoops and its free weights and its cut grass and sunshine. Everything orderly and looked after and every overall-clad prisoner looking lean and suntanned and contented and at ease.

‘Oh, yes, brother,’ De Boele continued, ‘you’ve made the right choice here. All of the paint you will ever need, all of the marble and clay and typewriters and pens and amplifiers and film stock. Three hot meals each day. A different Criterion film screened every night. The best stocked library outside of a national archive. That’s where I read your Willow Garden by the way. Fantastic book, it made me cry, I’m not ashamed to say.’

Pryce mumbled an attempt at a gracious reply and tried to keep the look of elation from his face.

‘I read more than I ever used to out there.’ De Boele pointed a thumb behind him and sneered as he said out there. As is it were almost beneath him to even mention it. ‘And I sleep better, and I eat better, and I’m in better shape than I’ve ever been, and I managed to kick the junk years ago while here even though you can get whatever you want and the guards couldn’t care less. It’s a paradox, my friend, all of it. When I was free,’ de Boele gestured a set of air-quotes, ‘When I was free, so-called, I was a junkie ego-maniac, shitty artist painting empty crap and trying to second-guess what my audience and my critics wanted from me. I lived in chaos with a needle in my arm and a bottle in my hand, anything to keep the endless empty misery at bay. Which is futile, as you know. A bottle in one hand, a syringe in the other, how are you going to hold a paintbrush, you know?

‘But in here, in so-called prison, I paint my best work, free, clean, healthy, at peace. I paint skilful work- whatever I want, however I want- and I am fit and I am happy, truly. Only in here have I finally found my freedom...’

Pryce felt the need to interject, to contribute, but De Boele was burning brightly as he spoke, burning with an energy that Pryce had never felt among his friends and his peers. It was as entrancing and restoring as a log fire after a long march through a frozen forest. Pryce felt the words warm him and remained silent.

‘… The idea of only having your labour but not the fruit of your labour, I only understood that when I got here. The idea that success is as bad as failure and that the more you know the less you understand, I only began to understand these things when I got here. When I gave everything up and became nobody, that was when the pieces fell in to place. You see...’

It went on and on this way- de Boele unleashing a testimony from the heart, not smoothed with practise and repetition, not laced with a grifter’s rhetoric or a motivator’s cadences, but just circling examples again and again, of the emptiness out there versus the paradoxical absolute artistic freedom of life in here, of life in The Programme. Pryce became drunk on the talk, his heart beat loud in his ears like the first time he smoked a cigarette as a teenager, like the first time he drank a cup of strong black filter coffee.

The two prisoners entered the canteen. De Boele did the rounds like a duke at a soirée, shaking hands with the elderly, hugging and swapped quick witticisms and in-jokes with the younger inmates and introducing Pryce to everyone.

A good number of them seemed to know of Pryce already- they had read The Willow Garden and Light Through the Shutters and more than one had even read his youthful, out-of-print poetry collection. And he knew some of them too- there was a fellow novelist who had killed a young boy in a drunken hit-and-run, a composer who had abused his position and supposedly several of his female soloists, and a guitar player who had famously strangled his manager with a low E string before attempting to kill himself via tranquillisers and high-end whisky. Those were the newspaper stories anyway. But here, now, they all seemed like great people- welcoming, softly spoken, amusing, attentive and engaged fully in the moment.

‘We’re gonna grab some food and I’ll fill Julian here in on more of the details of life in The Programme.’ De Boele gave Pryce’s shoulder a gentle squeeze. ‘We’ll catch you fellas soon, maybe play a few hands of poker.’

‘Sounds good.’ The Guitar String Strangler said. They all exchanged handshakes and back-patting half hugs.

Pryce and De Boele joined the short queue at the counter, collected their plates- today it was braised fillet of lamb with asparagus, dauphinoise potatoes and a red wine jus- and found a quiet corner table.

A quiet corner table- in a prison canteen. De Boele caught the look of utter confusion on Pryce’s face and smiled.

‘I know,’ de Boele said ‘I was the same way when I first got here. Dumbfounded. It’s almost beyond belief, isn’t it?’

Pryce looked around- at the clean tables, the high ceiling, the tasteful décor, the food that he would only able to get on the outside by making a months-in-advance restaurant reservation. If he strained he could just make out the respectfully quiet, amiable conversations- about cinema, about literature, about metaphysics.

‘How do they afford all of this?’ Pryce said.

‘Well, we pay for it, of course.’ De Boele said. ‘When you sign up for The Programme you give up everything you have- property, portfolios, future royalties and residuals. In my case, all my old works were auctioned off and a portion of what I create in here is passed off as the work of some bright new thing and then sold off. They will have all your royalties too. And of course the works of controversial, outlaw artists practically sell themselves. The foundation behind The Programme makes millions off us each year. Tens of millions.’

‘You know...’ Pryce took a bite of the best piece of lamb he had ever eaten. He leant back in his chair, closed his eyes and let out a contented sigh. ‘I really don’t care.’

‘I feel exactly the same way.’ De Boele said between mouthfuls of potato and braised meat. ‘They save us from ourselves with this set-up. We have all the materials and equipment we could ever need, we have infinite time to create without obligations, you can get whatever you could possibly need from the commissary, you can get access to the finest call-girls money can buy.’ De Boele gave him a mischievous eyebrow raise before turning serious. ‘Although money doesn’t really exist in here so everything is free. If you want something, you ask for it, and it’s brought to you. You soon stop becoming materialistic. Another paradox. So we are all equal here, we all wear the same clothes, we are not all vying for attention in the press any more. Envy is essentially impossible here. Like I said, this is paradise. What every artist spends their whole life dreaming of.’

‘And all you have to give up is your freedom.’ Pryce said.

‘All you have to give up is your freedom.’ De Boele adjusted the tilt of his beanie and leaned in closer to Pryce. ‘Hey, are you feeling alright?’

‘I, I...’ Pryce followed a chain of memories. The blown deadlines and day drinking. The sacking over the affair with the naive-eyed provincial girl. His wife filing for divorce. His reaction- rage and then cold nothing. The long, still minutes of standing over his wife’s supine body, her face a red concave. The dripping claw hammer in his grip. The officers. The handcuffs. The indulgent tone the doctor had taken with him. And you are wholly innocent.

Pryce cried out words that weren’t words, a rush of syllables whilst de Boele craned his neck to get the attention of one of the uniformed officers at the far end of the canteen.

Pryce sat at the desk in the corner of his cell, writing. Or trying to. The words weren’t coming, a line or two and then he would strike it through with a frustrated back and forth of black ink. He heard footsteps from out in the corridor- the steady click of work shoes rather than the muted taps of prison issue footwear. Pryce stood in the doorway of his cell and waved for the attention of the officer as he passed.

‘Excuse me, sir, would it be possible to get one of the computers de Boele mentioned and perhaps access to the vast library he told me so much about. You see, I’m really struggling to get this latest work off the ground.’

The officer smirked before adjusting his voice to become a subtle mockery of Pryce’s own educated accent. ‘Why, I shall have to make some inquiries, sir, but for a man of your stature I’m sure arrangements can be made.’ And then he walked on, shaking his head and laughing to himself.

The heel clicks grew fainter.

Pryce was alone.

They were often laughing, the officers, often sniggering or having little condescending remarks at the ready to greet any honest enquiry.

Sometimes, it was as if they knew nothing about The Programme at all.