On Attention, Addiction and Algorithms

Commonplace Newsletter #77

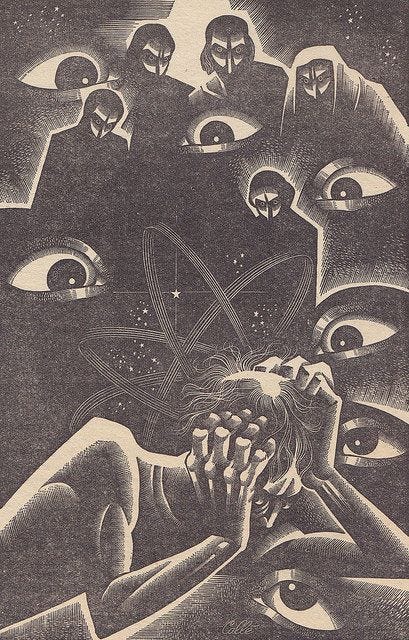

I believe that the events of the past couple of years- the pandemic and its social and institutional fallout- have been apocalyptic, in the sense that they have revealed what was once hidden, or at least what was vaguely intuited but never fully acknowledged. And that (mostly) unspoken truth is this- that we are all chained to our screens and our feeds; trapped, confused and near helpless.

Sure, there have been scores, thousands of articles and books published which have all wrung their hands about this topic- about how atrophied our attention spans are, how fractured and frustrated our discourse is and how impoverished our cultural and social lives are (or are becoming) as a result of the ubiquitous screens that are a constant part of our days from the moment we awake until the moment we eventually fall into some kind of slumber. This is old news. Passé even, a truism. But what is changing is the intensity to which these truths are being realised. Having been increased by the apocalyptic nature of Covid, it can no longer be ignored or brushed away or dismissed as being Luddite fear-mongering or hysterical naysaying.

See, the pandemic responses and their consequences have proven to be a great accelerant to what was already being undertaken, they added fuel to the already burning fire. Yes, we have been increasingly online and our lives have been increasingly screen mediated since the turn of the millennium1, but many Covid policies turned the heat up as far as it would go. Rather than us frogs2 being slowly boiled by spending more and more time each year scrolling feeds and reading content, Covid and its attendant lockdowns saw the collectives screen time take an unprecedented quantum leap. In April 2020 the average US citizen spent 13 hours a day looking at a screen. I’m going to say that again. In April 2020 the average US citizen spent 13 hours a day looking at a screen. This implies some spent a good deal more time than this glued to their devices. This is getting worryingly close to ‘every single waking moment’ territory. This is getting close to the Matrix and its human batteries moving from dystopian metaphor to quotidian reality.

And I was no different, by any means. My own daily hours of screen time during that first lockdown would regularly push into double digits- Twitter and the news upon waking, DMs and group chats once my stateside friends were awake and then an old film or TV series once I felt I had reached my daily threshold of despair and speculation. And I was fortunate enough to be deemed an ‘essential worker’ meaning I was still able to go out into the real world and commute and socialise with colleagues on shift. Without this reprieve I would’ve become a thirteen hour a day scroller I’m sure.

But even with this mitigation my ability to focus on physical books and my time spent doing so plummeted. My writing practise became virtually non-existent3. My creativity and desire to create fell to an all time low, in spite of my abundant free time. Something had changed within me. And like the lockdown beer gut I was cultivating, this was a transformation in the wrong direction.

II

“To pay attention, that is our endless and proper work”

~Mary Oliver

I always prided myself on my attention span, and I can say that any success I have enjoyed in life has largely been due to this cultivated skill. Now some of this is perhaps innate- my parents will tell you that even as a boy I was able to sit still in silence and contentedly read a book or watch a video for hours- but the fact remains. See, unless a task or an undertaking can be focused on, the end results of your efforts are going to be patchy at best. Your ability to attend to the task at hand is vitally important- which is of course obvious- but like most obvious things it is not acknowledged or given its due anywhere near as often as it should be.

In fact I would argue that focus is the springboard for all other skills. It is the prerequisite for everything. If you cannot pay attention to the problem at hand then the problem at hand will remain unexamined and thus unsolved. It is not a lack of energy or will or desire or ability that leads to a project’s downfall, it is the inability to see it through without being distracted by something else. So to be able to pay attention to a task is the initial step and it is a step that many of us are unable to make, or to make for any effective length of time.

At first I thought that my gradual loss of this skill might be a mere consequence of aging, of not being as cognitively spry and youthful as I had been during all of those childhood and teenage reading sessions late into the night. Maybe the fault was mine, maybe this dwindling ability to focus was a mere fact of human nature that I was blaming external forces for rather than accepting. Perhaps I was using tech and the internet and social media as convenient scapegoats.

But then I looked more deeply. In conversation people would reveal that their attention span had also dwindled over the past five to ten years or so, and some of these people were still teenagers. Hardly anyone I spoke to read books for pleasure anymore, and even those who had previously been voracious readers now had to actively force themselves to do what had once taken little effort.

Many would make light of their scatterbrained nature, about the perils of managing emails, messaging obligations and multitasking. There was always a wry smile and a shrug, expressions that said ‘meh, but what can you do?’ What I saw as something of a personal crisis- why do the increasingly rare books I read wash over me? Why does my mind feel like a sieve?- others seemed to accept with a bored equanimity.

It was baffling that everyone intuitively knew that mass attention was on the wane yet only I seemed to be concerned.

But as I dug into this further it turned out that I wasn’t the only one.

III

“Our conventional response to all media, namely that it is how they are used that counts, is the numb stance of the technological idiot”

~Marshall McLuhan

As I said in the introduction there have been many, many books and articles written on tech-induced attention problems. They have spawned into something of a journalistic sub-genre- of which you could argue this essay is an example- whereby the writer, appalled about how much of a news feed junkie/Twitter zombie they have become, vows to give up their smartphone/social media/the internet for a set period of time, usually a month. They talk of digital detoxes and use all of the addiction terminology such as: dependency, withdrawal, relapse and so forth.

I had always been suspicious of this as I have found that when one decides that a habit that they previously saw as being morally neutral is now a problem then the language of addiction seems to naturally follow. I have known people contentedly play computer games a fair amount until they decided it was a waste of time and suddenly they were ‘hooked’ and needed to ‘detox’.

So I was cynical and dismissive of the idea that something as ubiquitous and so normalised as the internet could be legitimately addictive. I wasn’t a nerd and so the idea of screen based information being addictive seemed preposterous, and so I closed my mind to it. Which in itself is a classic form of addict logic. As William S Burroughs once observed, every junkie starts out with a fear of needles. Every junkie in training thinks they are different, thinks that they can handle it where millions can’t.

My rationale, my argument with myself was this. Those article writers who I had come across had all been tech writers, Silicon Valley insiders or the kind of journalists for whom constant feed reading and tweet posting was a contractual obligation as well as a means to gain attention for themselves. And so I wrote them off as a separate breed rather than being mere case studies for what was soon to become commonplace. Until I noticed the same problems that they complained about manifesting in my own life.4

I’ll quote Nicholas Carr, whose 2011 book The Shallows, the classic (and prescient) contribution to the ‘tech has ruined my attention span’ genre:

“Over the past few years I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming my memory”

The amorphous, creeping nature of this change is what unsettled me, just as it did Carr. He continues:

“[In the past] I’d spend hours strolling through long stretches of prose. That’s rarely the case anymore. Now my concentration starts to drift after a page or two”

So far, so familiar. And then comes the most accurate description of this phenomenon, via an analogy that truly resonated with me on first reading:

“What the net seems to be doing is chipping away at my capacity for concentration and contemplation... Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a jet ski.”

This is it in a nutshell. Rather than luxuriating in prose, in ideas, in actual books, rather than enjoying leisurely exploration at depth, the hunt for information is now an endless high speed skim- a bouncing from topic to topic where nothing much is retained, let alone internalised. All inputs now seemingly exist on the level of mere information because to internally transmogrify them into knowledge, let alone wisdom5 takes a level of sustained attention and reflection that the lure of said endless information has largely robbed us of.

Hence my suspicion that the screens which present this information may be legitimately addictive. The endless, fruitless hunt for more and more rather than being able to enjoy a reasonable portion at leisure is addict behaviour. Or, to be more specific, it is behavioural addiction.

IV

“Addiction is a deep attachment to an experience that is harmful and difficult to do without. Behavioural addictions don’t involve eating, drinking, injecting, or smoking substances. They arise when a person can’t resist a behaviour, which, despite addressing a deep psychological need in the short-term, produces a significant harm in the long-term”

~Adam Alter, Irresistible6

The idea that a behaviour can be addictive seems strange to those who have been conditioned to see only external physical substances- whether it be crack cocaine, heroin, alcohol, cigarettes- as being addictive. But if a behaviour- playing computer games, gambling, scrolling and posting on social media- illicits a neurochemical response and makes the individual feel good then it can become addictive. Especially once we begin to turn to this behaviour as a salve for our psychological troubles. When the brain learns that the behaviour lessens the pain or the anxiety or the loneliness, we learn that the behaviour is now vital to our emotional stability, that is when addiction becomes established.

Addiction- whether to a substance or a behaviour- is complex, it isn’t just about your physical response. It’s about how you interpret that physical response psychologically. When the response becomes a crutch, when it becomes a way to get through the day addiction is now able to take hold.

And what could make the mass of people reach for a behavioural (or indeed chemical) pick-me-up more than the fear, confusion, anxiety and depression that comes with being bombarded with constant news that a deadly virus is coming? And what could make people turn to the addictive behaviour of social media scrolling and endless online information hunting than being compelled to stay at home all day for weeks on end because of said virus?

That 13 hours per day screen time average starts to make sense.

The neurological mechanisms in humans were already in place. The external event- Covid19 and the global response to it- affected people mentally in a way that lead to them deeply wanted a psychological salve for their troubles. People were positioned to become addicted to substances and behaviours. And our screens took centre stage to fill this need, because as well as being omnipresent, they have also been carefully and deliberately designed to be very, very addictive.

V

“The problem isn’t that people lack willpower; it’s that there are a thousand people on the other side of the screen whose job it is to break down the self-regulation you have”

~Tristan Harris

Scoring drugs is not easy. You need cash money, you need to physically go to where the dealers are selling with all of the attendant risk of being robbed or beaten7, and of course possession is illegal which means there’s a chance of being arrested and thus separated from the possibility of getting high.8

Now contrast this method of changing your mood to scrolling and surfing. All social media sites are free. Virtually everyone owns a smartphone, a tablet, a laptop, a desktop. Data is cheap and connection speeds are getting faster every year. Internet use- even chronic use while other humans are present in the room- is entirely accepted and normalised. It is ubiquitous. There is no moral stigma towards scrolling, swiping and surfing, even if you do it A LOT.

Our society runs on this infrastructure. The Silicon Valley companies at the heart of it all are collectively worth trillions. Our (over-) use of their products props up the entire economy such that some sort of neo-Luddite revolt, if even marginally successful, would cause complete economic collapse. In fact, if we all simply turned off our devices a little earlier at night and insisted on regaining the hour extra sleep that we have collectively lost since the dawn of the electronic age, the whole financial system would be devastated. It’s not just Netflix who consider sleep to be their primary competition. All of the Silicon Valley giants do, at least implicitly. Which is to say that on some level they consider you the consumer and us the public to be the competition. To be the enemy. By definition.

It’s the classic contemptuous view that the pusherman holds towards all of the dope fiends that he makes his fortune from.

At heart, this is an environmental issue. With such gargantuan sums of money and world changing amounts of power and influence at stake, every tiny facet of the online environment has been engineered and meticulously tested to garner maximum engagement, which is to say to illicit maximum levels of addiction. They call us ‘users’ for a reason.

When your entire business model is to offer the unlimited use social media app or website for free and to make money via advertising placements on it then ‘Time on Site’ becomes the only metric that matters. All you care about is eyeballs- and yes, that word is telling, as it conjures up the image of Alex in A Clockwork Orange with eyes clamped open as he is forced to continually watch images that he would rather not.

Nothing on the internet today is accidental. Thousands of tests with sample sizes of millions of users are run every week to increase the addictiveness of the online environment in question- from colours, to fonts, to audio, to how to make everything run as smoothly and as friction-free as possible. Friction is the enemy of this model, because the connection between stimulus and response is more effectively ingrained when those things occur in rapid succession. If the rat is consistently given the food pellet the instant he presses the button then he will be quicker to realise that button= food and so begin to press it compulsively.

This is why the online world was seemingly less addictive in the past. As well as being less engineered it was also slower, and the relatively long loading times for certain pages and images disrupted the stimulus = response connection before it could fully take hold. But this speed limit, as it were, has now been entirely overcome unless you live in a very, very remote and secluded part of the world.

And technologists know this. They understand how both the online environment and the real world environment can be potent cues for addictive behaviour9. This is why the children of the Silicon Valley elite are usually sent to fee charging independent and elite schools where screen time is severely restricted, if not outright prohibited. And the same rules are enforced at home. Like the pusherman, these technologists live by the classic dealer principle of ‘don’t get high on your own supply.’

Now, the literature on exactly how the increasingly addictive features of social media came into being is as vast as it is well documented. For example Aza Raskin, the creator of the infinite scroll has publicly expressed deep regrets regarding his invention. Infinite scroll increases time on site for twitter by 50 percent (which may well be an underestimation). Raskin has calculated that his invention has lead to people collectively spending over 200,000 entire human lifetimes more time scrolling online than they would have done had he not created it. This is billions of hours that humanity would have collectively spent doing something else.

Like the inventor of the ‘like’ button and other such innovations before him, I suspect that Raskin feels no small amount of guilt for the consequences for what he has brought into being.

VI

“I tried to pay attention, but attention paid me”

~Lil Wayne

Now we could spend all day moaning about these meticulously tested features that are designed to get you hooked. But to do so, and to lobby for the removal of any such features is to in a sense merely play a game of Whack-A-Mole. The real problem goes deeper. The real problem is the wrongheadedness of Behaviourism, the rat and pigeon bothering branch of psychology that undergirds all of these bells and whistles10. Reward and punishment, upvotes and downvotes, follower numbers and other forms of ‘engagement’ are great means of modifying behaviour and making advertising revenue but they are terrible ways to contribute to a society. Reward and punishment and ones and zeros, and human flourishing and human creativity is a question of much more than ones and zeros, on and off, yes and no.

Such simplistic, unnuanced, binary thinking, embedded into the very fabric of our online life via mysterious and secretive algorithms that are optimised for this addiction forming ‘engagement’ above all else leads to an impoverished culture filled with low attention span ‘users’ and ‘consumers.’

I believe it is impossible to ever create Artificial Intelligence that can equal the human mind. However I do believe that it is possible to strip humans of their attention span and ability to create in such a way that AI programmes start to look pretty sophisticated by comparison. And further, I believe this is what is happening.

See, creativity is dependent on being able to enter what the late Hungarian-American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called a ‘flow state’. Flow is the mode of being where you lose track of time due to being so absorbed with the activity at hand. Such flow is not only when human beings are happiest, according to Mihaly, but it is also an intrinsic part of mastering any discipline and excelling at any creative endeavour. And like all other forms of paying attention it is decimated by what our screens have become.

Mihaly argued that reading a book is the simplest and most common form of flow that the average person experiences in their life. And now the proportion of Americans who read books for pleasure is at the lowest level ever recorded. But people still read, you might say, the just read on screens now. This argument is a misnomer.

I would beg to differ. What I see happening- and what I have certainly experienced myself during my own spiralling screen use during lockdowns- is that people now spend their time consuming and reading ‘content.’ Content conforms to the logic of algorithms and the optimised for engagement attention economy they have brought into being. Individuals with diminished attention spans create easily digestible content for other individuals with diminished attention spans which results in everyone’s collective attention spans further diminishing. The more successfully you can use engagement tactics to grab the lapels of the short attention span public, the more you can ‘monetise’. And the more people do this, then the more time we all spend on our screens and the deeper the collective behavioural addiction becomes.

It’s a race to the bottom, at least in the aggregate. In the same way that unnutritous junk food keeps you hungry, which makes you eat more which further ruins your metabolism and waistline. So too does this ‘snackable’ online content further remove your desire and indeed ability to focus on reading a full length book. Instead, feeling perpetually vaguely bored and restless, we carry on searching and scrolling, on skimming the surface looking fir something that we no longer have the ability to attend to even if we were to somehow find it.

VII

“Control of consciousness determines the quality of life”

~Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

But all hope is not lost. Here I am going on and on about the collective atrophying of attention span, and you are still here with me over 3500 words down the line. Our attention spans may not quite be what they were but they are not completely shot. Not yet anyway.

This makes me believe that there can be some sort of oasis of art in the desert of content11, that it is still possible to mount some sort of ‘attention rebellion’ (to use Johann Hari’s phrase).

Now, in the ‘writer laments their spiralling internet addiction’ sub genre that I mentioned above, the standard conclusion is to note how refreshing their offline ‘detox’ was and to breezily recommend some tools and strategies to keep their internet use to an acceptable level. This is environmental modification to try and disrupt that well-worn and smooth connection between stimulus and response. You will hear talk of things like: turn all notifications off, never take your electronics into the bedroom, buy a phone safe with a time lock if you have to and definitely install addiction curbing software such as Freedom.

There is some merit to such actions, but to me they smack too much of ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps’ self-flaggelation. As Harris said, it’s you versus a thousand highly educated, well compensated Silicon Valley programmers on the other end of the screen. So putting all of the onus and blame for your addiction purely on your own shoulders seems misguided. I suspect that in coming years, given the quantum leap in screen time that Covid brought about that, there will be more talk about reform and policing of social media and its algorithms on a governmental level. Whether anything comes of this, and whether such action proves to ultimately be beneficial remains to be seen, but I do think it will become more of a talking point. Assuming of course that people have enough attention span left to even make such proposals viable and coherent.

Like I said, attention span is the most important issue because it is the pre-requisite to tackling any issue at all.

So the above solutions, both personal and political can help us regain our attention. At least in theory. But they both exist on the level of the removal of the bad. What is better, I believe, is the addition of the good. This is why I mentioned flow earlier, because flow is the good. Reading books is good because it reminds us of what flow looks and feels like. Knowing this and honing this, we are able to create- truly creative- without feeling the pull of our emails and timelines and without feeling the need to conform ourselves and our work to the engagement tactics that the algorithms try and nudge us towards.

Having been reacquainted with flow we realise that creation and mastery is an end in itself rather than a mere means to make metrics move. And as we act in this manner we attract others who feel the same way, who are also acting the same way. We regain our focus more and more. We do our little bit, in our own little corner to reverse the attention span downward spiral and instead create a virtuous circle.

That’s my hope anyway. And whether it works or not, it’s surely better than staring at a screen and scrolling all day.

Until next time,

Live well,

Tom.

Or since the mid twentieth century if we include the original screen- television- into this discussion.

The word ‘frogs’ now has a political connotation of being someone who is young, right-leaning and uses their time and energy to make dissident memes concerning the people on the other side who run things. This is not what I am referring to here. However, the fact that I know about frogs and about myriad other US culture war things despite being both English and deeply ambivalent about them is indicative of my having spent too much unhappy time online. Which in itself gives weight to the thesis of this essay.

Indeed it was as a result of this lockdown fuelled creative slump that I finally decided to dust myself off, regroup and start writing the Commonplace Newsletter, with the first issue being published in early August 2020.

I should note that though I am now a professional writer- in that these essays and related activities are how I earn a living- this situation is a recent development. And the withering of my attention capacities began before this time when I worked a non-computer, non-writing-related job. All of my internet use was thus entirely optional and I had none of the professional obligations that ‘knowledge workers’ could cite as mitigating circumstances for their internet addictions.

For the record I would argue that information is something you receive like a fact or an opinion (whether it is true or false is largely irrelevant here), whereas knowledge is information you have internalised and internally verified. Wisdom then is knowledge that you have verified by actual lived experience, usually over the course of decades. So in this hierarchy information should only be the beginning and true learning is thus the verification, application and internalisation of various inputs over time. Being stuck at the level of perpetual information seeking is a warning sign that something is amiss, in my opinion.

Though this is far from definitive, I would list Adam Alter’s Irresistible, Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows, Jaron Lanier’s 10 Arguments For Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now, Sherry Turkle’s Alone Together and Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus as all being essential books to read regarding the themes discussed in this essay.

I am aware that, as with many other things in life, rich people have their own safer and classier way of procuring narcotics. But you catch my drift.

At least in theory.

I didn’t want to get too bogged down in psychological terminology during this essay but I should take a moment to make the distinction between addiction and dependence. Addiction, which is what this essay concerns, is more concerned with the users emotional and psychological ‘need’ whereas dependence concerns the physical need where withdrawal symptoms stop place when the person stops using. So it is possible to be addict but not dependent on something just as in theory one can be dependent but not addicted. Although of course both states often co-exist. Research currently points towards Social media etc being additive but not dependency forming.

As I pointed out in an earlier essay I think the fact that B.F. Skinner- the father of Behaviourism- wrote a book called Beyond Freedom and Dignity is hugely telling.

This pithy little phrase has been my ‘bio’ on twitter for some time now. It serves as a continual reminder to myself about what my online priorities should be.

Excellent as always.

The point about “flow” here is the be all and end all for me. I feel anxious if I don’t get that feeling at least once a day. I don’t think it’s good for us on any level to be perpetually distracted and unable to concentrate.

I suspect an uptick in anxiety disorders have directly resulted from our shot attention spans.

Protect it at all costs.

I think the bit about addition you have at the end is crucial. Simply "quitting" a habit is dangerous, because you create a void in yourself that must be filled. If you don't fill it with something good, something worse will come along to take the place of what you removed. It might be a more extreme version of the old habit, or you might go from smoking cigarettes to shooting heroin.

With behavioral addictions, I think a lot of this occurs through spiritual growth. We can recognizing that satisfying our emotional needs through an addictive behavior isn't good, but creating or finding new ways to satisfy those needs is difficult, because it involves self-transformation. Sacrifice, death and rebirth, etc. You can't rewrite the rules of your own way of being just by thinking about it really hard (as much as I wish I could). A spiritual journey is necessary to undergo such transformation.