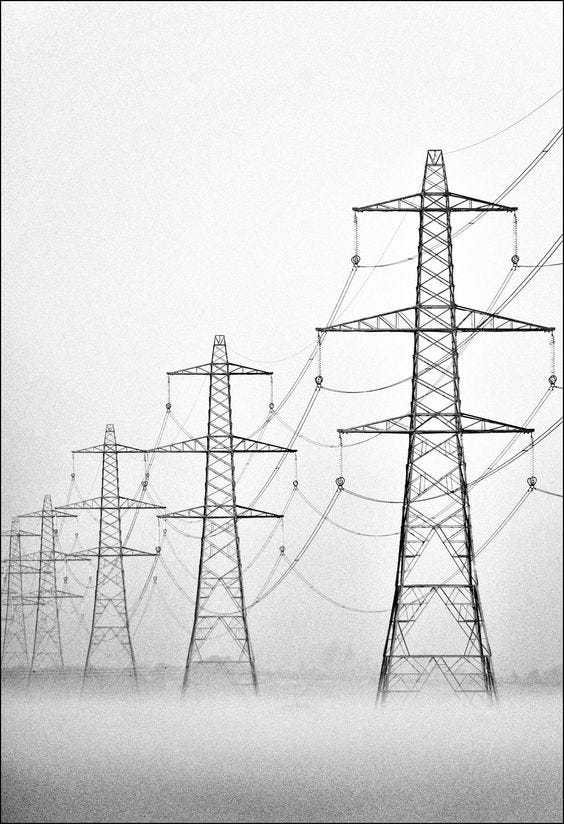

Pylons

Commonplace Newsletter #103

It was enough to give you nightmares. First the crackle of electricity as we see a close-up of a frightened rabbit, eyes wide, ears pricked back, tense, alert. Next purple streaks of electricity climb up a giant pylon standing sentinel in a green field, the sky above clouded and purple and ominous, the background music a low orchestral swell full of foreboding. With the groan of bending metal the vast structure then creaks to life and jolted with electricity it begins to move. Like Frankenstein’s monster this vast creature- this terrifying metal scarecrow- should be inert but the surging lightning bolts of electrical current bring it to life. It unmoors itself from the earth and begins to walk. The rabbit flees. The monster- faceless, eyeless, heartless- stomps to freedom and lurches to its lifeless brothers who it awakens by shooting a purple lightning bolt from his metal arm to theirs.

I was maybe four or five years old when I saw this advert1 on the boxy black telly in the living room. The idea being sold- that National Power were building new state of the art gas burning power stations that would be more efficient while generating less emissions- was lost on me. In the years to follow I didn’t even remember that there was a voice over at all- an avuncular, cut-glass vowels English accent that I suspect has now died with the last of the Silent Generation men and women who spoke it. All I remembered was the horror. As the ad progressed the music became somewhere between hopeful and triumphant and in the end the army of walking pylons congregated on a cliff-edge to wave to a similarly sentient off-shore oil rig named Derrick. But the levity and the hope and the bad pun escaped me. As I said- all I retained from this formative viewing experience was the horror2.

But then I grew older and didn’t really think about it anymore. During my childhood my dad worked for the local electricity board and so I would see plenty of substations throughout those years, plenty of high voltage lines and bright yellow Danger of Death signage where a collapsing black silhouette of a man was struck by an N shaped thunderbolt, but none of these things registered as out of the ordinary. It was the pylons that held the grim fascination, these towering figures on the edge of town, these man-made metal giants that looked out from fields on family car drives in the countryside and which no one else seemed to really notice or care about.

Now over these small hills, they have built the concrete That trails black wire Pylons, those pillars Bare like nude giant girls that have no secret

The Pylons by Stephen Spender3

The pylon as an invention, as a ubiquitous piece of design is still less than a century old. It says something about our accelerated world that something so new, relatively speaking, can seem so ancient. As if there was never a time before it.

But there was. Before 1928, before the Milliken Brothers from the USA first stepped up to their drawing boards, and before the supposedly anti-modernist architect Sir Reginald Bloomfield suggested design tweaks to make the giant skeletal structures palatable to interwar British sensibilities and tastes, the English landscape was- if not pristine- then at least a significantly less visually cluttered place. Before pylons modernity had scarcely touched the countryside. Rural England had a timelessness to it, a deep continuity.

It was a place, as Spender implies above, that held secrets or that at least had the capacity to allow for lives to be led in a quiet, unobserved way, unconnected from everything apart from the actual physical environment and your immediate neighbours. Whether that represents a bucolic paradise or a nightmare of rural isolation is up to the reader to decide.

The point is that for as much as the Millikens and Sir Reggie might have championed the classical design principle that good design should be unobtrusive4, pylons have left an indelible mark of the modern world across ancient fields and byways.

Few would question the necessity of what they brought into being and the fact that creating a unified national power grid was not only an inevitability but also a ‘good thing’. The electrification of the home lead to whole categories of new inventions which has culminated in the home computer through which I am communicating with you right now.

But every decision has consequences and every step in the march of progress sees something trampled underfoot. When you are given something with one hand, something is inevitably taken away with the other. This is just the nature of things.

Now, it is seemingly a rule of contemporary essay writing that every time the topic of technology and progress is broached the writer must take a hardline stance advocating for either a wholesale return to tradition (however blindly romantic and impractical) or an unblinking, gleeful sprint to whatever lays at the terminus of the technocratic AI / VR/ transhuman superhighway (however potentially catastrophic for human life and the human experience). Well, I’m not going to do that. Speaking for everyone and speaking in absolutes is the way of the would-be tyrant. I don’t know what’s best. But I do know that the ancient countryside holds a wisdom and a truth that is beyond whatever technology we have or will ever have. Cycles of progress and regression play out against the backdrop of the endless continuity of the natural world.

Until next time,

Live well,

Tom.

And if you read the comments section beneath the video for the advert I linked above you will see that many other children of my generation were likewise scarred, some even developing genuine aversions and phobias of pylons and power lines. Others loved the ad and were enchanted by the (supposedly) friendly living pylons, but then there is no accounting for taste is there?

The rest of the poem- which is not especially good, truth be told- can be found here. I quote it because it is demonstrative of the contemporary artistic sentiment which has a way of being buried by the march of progress if it is not lockstep in favour of it. History being a narrative that is written by the winners – their way.

This is number five of designer Dieter Rams’ legendary 10 Principles of Good Design. Rams may have written his ‘commandments’ around 50 years after the pylons creation but his 10 principles are an exercise in codifying and simplifying a philosophical thread in design that can be traced back to the very start of modernism, if not before.

Someone should have made a Doctor Who episode wrapped around the concept of sentient pylons. Maybe they did. I'm struck by the idea of pylons as electricity bridges, or at least the pylons that hold those bridges aloft. Also, I'm struck by how different people interpreted the same set of images.

Later we designed wifi towers to look like trees, and I'm not sure that's an improvement to design that shows the bare engineering. I wonder what the pylons would have looked like if more intentionally designed by the sorts of people who talk about intentional design. Again, that's not to say it'd be better or worse, but why we've decided to stop designing them is an interesting question.

A note that street rigging for construction sheds in NYC has been redesigned and though more expensive, is actually successfully more lovely and 'architectural', you feel like you're moving through a public space rather than a condemned alley.